(This post first appeared in the free grape wall newsletter. Sign up here.)

Is orange wine the new red wine?

Grape Wall newsletter recently made a case for orange wine aka amber wine aka skin-contact wine in China.

The tannins, qveri (clay vessels) and history of places like Georgia can resonate with consumers in a market where few regularly drink wine and the current red wine strategy is stagnating.

We already see proof of interest in orange wine from consumers and critics. And local producers are already making them, far more than most observers realize.

I won’t claim orange wine will save China’s wine market, or outright replace reds, but its advantages are plenty. In fact, what might save the market is those qveri!

More on that below.

PS I know qveri in Georgia and the clay vessels in China are not identical. I am using it as a general term. I also know not all orange wines are made in clay vessels. Etc. Okay, on to the wine!

Orange is Already the New Red?

For some people, orange wine is the definition of wine. Or, more generally, the niche that includes everything from natural to biodynamic to orange to pet-nat wine is wine.

These drinkers began their “journey” with such wine, maybe at the many specialist bars in Shanghai, and a big oaky red is as weird to them as an orange wine might be to a lifelong Bordeaux, Napa or Barossa fan.

When you consider wine consumption per capita is less than half a bottle per year in China, it means there are very few regular wine drinkers here, thus it is fair to question the trade’s focus the past few decades on red wines. And to see that the destiny of wine in China is up for grabs and consider what role these alternative wines might play.

(And don’t get me started on the “but red is a lucky color” observers.)

Orange Wine Attracts Drinkers

In my last newsletter, I lamented how the annual Hilton Food and Wine Experience in Beijing, once the city’s best wine event, went from two floors, 1000-plus labels and a raucous atmosphere a dozen years ago to a sedate and far smaller event this year. It felt like opportunity lost, given the successful craft beer, whiskey, burger, jianbing et al festivals we see in Beijing.

But one wine festival in Beijing has stood out the past few years: a crowded nine-hour orange wine festival held last year on a basketball court in downtown Beijing with a dozen importers, 119 orange wines, nonstop music, food vendors, and gift bags with tasting glasses. (Video here)

The crowd was young. Paid an entry fee. Was interested in the detailed tasting notes in the gift bag. And diligently worked through the booths. Excellent.

(See here for a deep dive into this event.)

And there are other festivals either dedicated to or including orange wine, especially in Shanghai, as well trade fairs, notably the Living Wine and Young Generation China Wine areas at Veronafiere’s annual Wine to Asia in Shenzhen. Thus, we do have some strong evidence of interest in such wines.

Orange Wines Taste Good

There was plenty of criticism of niche wines — natural, biodynamic, orange et al — when they first started to ascend in China about a decade ago. Mousy. Battery acid. Oxidized. Gross.

But that has receded as quality and acceptance increased. And we see a growing number of local producers focusing on these niches, including among members of Young Generation China Wine.

But bigger established producers are also getting involved and making some of the best orange wines.

Domaine Charme in Ningxia is known for its Viognier and released an orange version that Shuai Zekun, critic for jamessuckling.com, ranked in his top ten for China for 2022.

“It was genuinely outstanding,” he said in this Q&8. ‘Last year, I tasted nearly 8000 wines from all over the world, and this skin-contact Viognier still shines among its orange wine peers.'”

In 2023, a Rkatsiteli from Puchang was among my favorites of the year. Fermented via wild yeast. With sixty days of skin contact. No sulfur added or filtration before bottling. A complex wine that managed to deliver a fruit shop’s worth of aromas and flavors.

And Domaine Franco Chinois came out with a half-dozen experimental skin-contact wines in the same year.

The Muller-Thurgau had refreshing acidity and light easy tannins, with ripe stone fruit and hints of tropical fruit and candied ginger. Refreshing, with a pleasant tartness.

And the Riesling: fresh and light and juicy and easy-drinking, with hints of gingerbread, tangerine and nuts, and cloves lingering at the finish. (When your notes say “super fun”, it gives an idea of a mood evoked.)

The point is that local producers are not just dabbling in orange wines but also excelling at them.

And they have emerged countrywide, from Yunnan to Shandong to Shaanxi, including Runaway Cow, GreatWall (top-notch Longyan), Xiaopu, FARMentations (intriguing Black Muscat), Chateau September, Gloriville, Longting and The Starting Point, among others.

The degree to which these wines excel will depend not only on consumer demand but also on the industry pushing these as more than a novelty, because they have some nice marketing twists.

Tannins Evoke Tea

One twist is the tannins. When I enjoy Italian, Slovenian, Greek, Georgian and more orange wine with friends in China, they often agree the tannins have similarities with those in teas, especially in contrast to those in oaked wines. Even people used to drinking more commercial wine, and who find orange ones weird at first, note this character.

Taking a step sideways, the tea-infused pet-nats by Lingering Clouds in Ningxia are well-received at my tastings. Last year, winemaker Liu Jianjun made five versions, using Chardonnay as the canvas –Jasmine, Longjing, White Peony, Oolong and Black.

Intriguingly, each expresses the flavor, aroma and tannin of its particular tea. The Jasmine is fragrant, the White Peony juicy and bursting with flavor, the Oolong mild and smooth, and so on. And we see more producers working with tea infusions. (Overseas importers have also asked me how to get their hands on such wines.)

The point: there is something enchanting and delicious about this relationship between leaves and grapes, teas and wines. And ample cultural significance, too. I think this is a fruitful area to explore, including with orange wines.

Qveri Inspire Curiosity

As with the tannins, the use of qveri resonates, given clay vessels are used for traditional alcoholic beverages such as baijiu and huangjiu aka “yellow wine”, both with loyal followings.

This is a convenient point for explaining orange wines from nations like Georgia, where qveri are buried up to their necks, an idea easy to grasp. I’ve seen many videos on Chinese social media of clay vessels, partially or completely buried, being unearthed and opened to reveal aged spirits.

It’s an added bonus that China is a nation obsessed with its long history. The fact Georgians have been using the same techniques for more than 6000 years ago is incredibly impressive.

And Qveri are Convenient

Qveri also offer logistical benefits for local wineries. Barrels are expensive and time-consuming to import. And attempts to make wine with barrels from the China-North Korea border have delivered some rough results, based on what I have tried. (Garage winery Jiangyu in Shandong is currently doing experiments. Maybe it can make a breakthrough!)

Procuring barrels also means many decisions, from size to source to toast level to [fill in the blank]. And in a market where sales are not following, all of these factors add up to a burden

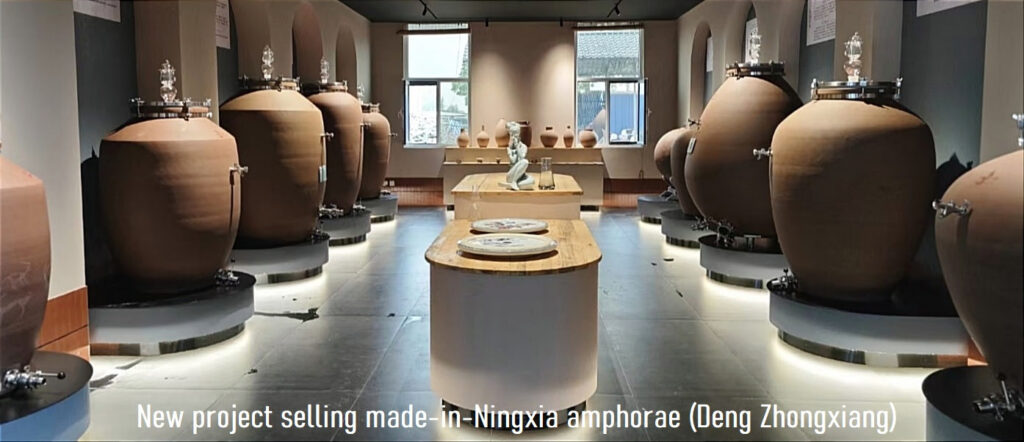

Qveri are an easy alternative. They can be made locally and easily procured–see photo above of a shop in Ningxia.

Yes, they are not perfect–I’m told they can be difficult to clean. But they are becoming common in China. A half-dozen years ago, I might be surprised to find qveri at a winery. Now I enter the cellar and wonder where those vessels are hiding.

Here’s the thing: this goes beyond orange wine. Last month, I attended a wine tasting in Beijing and found a pair of qveri-aged Cabernet Sauvignons, from Longyi in Ningxia, vintages 2013 and 2015. I was surprised at how smooth and easy-drinking these were. How they felt like an easy entry into the world of wine than most of the reds out there. And how maybe, just maybe, this is a way to broader appeal.

Which reminds me: on my last major tour of Ningxia, a winemaker at one stop showed me all of the qveri in the cellar. Then mentioned that more than 10,000 liters of red wine were hiding inside. Feels like time to follow up and organize a taste test with some fellow consumers.

Grape Wall has no sponsors of advertisers: if you find the content and projects like World Marselan Day worthwhile, please help cover the costs via PayPal, WeChat or Alipay.

Sign up for the free Grape Wall newsletter here. Follow Grape Wall on LinkedIn, Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. And contact Grape Wall via grapewallofchina (at) gmail.com.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.