I first met Tim Hanni when he visited Beijing just after The Wall Street Journal labeled him as the wine “antisnob.” I organized a dinner with him and some food and wine writers here, and posted about it 12 years ago this very day.

Hanni trained as a chef, became one of the first two U.S. Masters of Wine, in 1990, and has spent decades arguing that many of the trade’s ideas about taste are wrong and lessen the experience of consumers. He’s been known to call food and wine pairing “bullshit.”

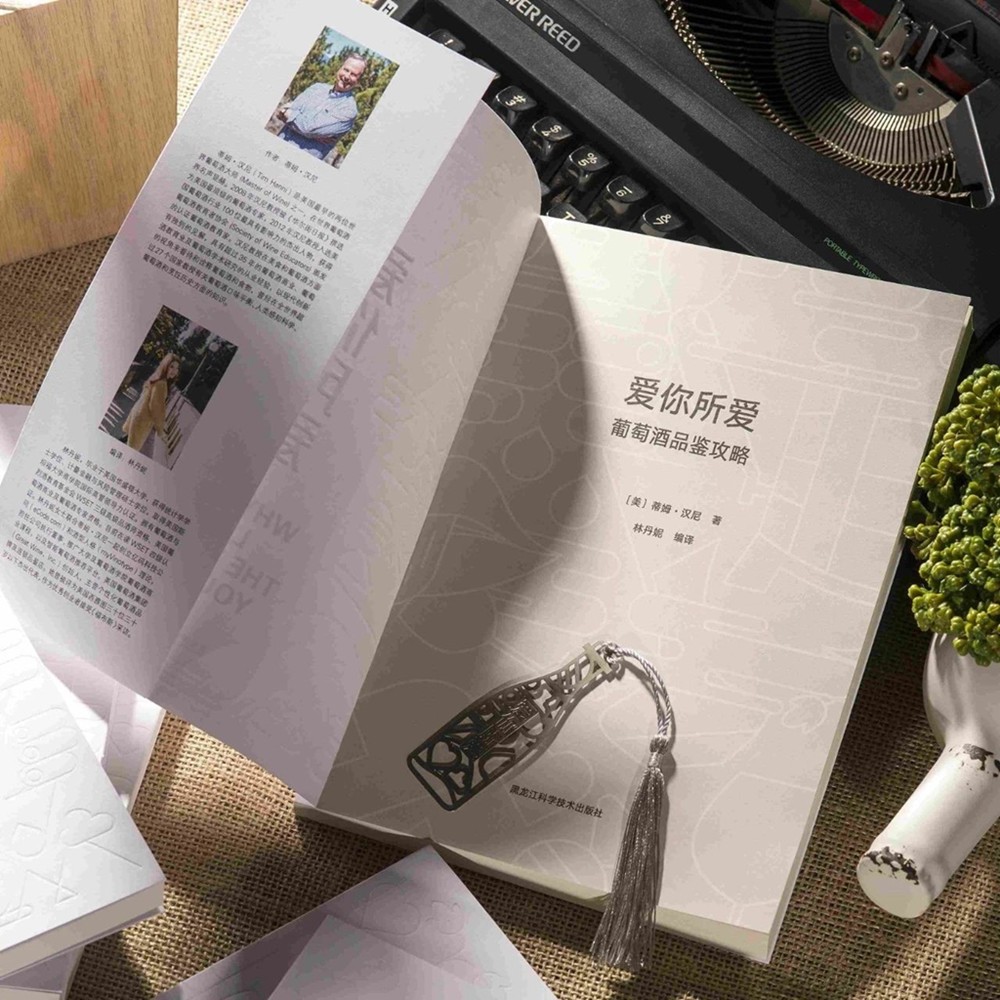

A Chinese edition of his book Why You Like The Wines You Like was just published, with revisions to account for the experiences of consumers here, and I asked him about that and his philosophy. (More about Hanni’s background here.)

JB If someone asked you to describe the book in 100 words, what would you say?

TH This book is about changing the “status quo” of wine enjoyment in a way that honors and empowers all wine consumers to drink the wines they love the most. Not necessarily what the “experts” like but what you like, from the heart.

With 50 years of my own learning and passion for wine and gastronomy, this book covers my 30 years of intense interest in why even wine experts may have completely different views on any given wine or combination of wine andfood. It covers my background in the industry, coming from a very “classical” background, and shares my insights on the slow erosion of wine facts, how the essence of personal enjoyment has been lost, and also the research into sensory and perception sciences.

Two of your slogans are to “drink the wines you love the most” and “respect the wine preferences of others.” How much do those apply to China, where we see a rising number of educators, key opinion leaders and critics as well as wine consumers?

Personal enjoyment–and experts dedicated to guiding consumers without arrogance or intimidation–is a lost art where wine is concerned. Wine education today, in China, France, the U.S. and all around the world, is seriously flawed and missing the most important thing of all: perception is personal.

Many wine lovers are excited to learn what wines experts covet, seeking new wines to discover and also travelling — either in reality or through books, podcasts and the like — around the world. But a vast number of people feel “forced” to like certain wine that they may find too strong, too bitter, too sweet, not sweet enough… the list is very long.

I want people in China, and the rest of the world, to have the freedom to stand up and demand that wine experts and professionals focus more on learning about the individual–and why different people like the things they do–instead of blindly expecting, “Well, I am an expert so you must like the wines I rate highly or suggest.” The core of this information is to give consumers a better understanding of themselves and others and, very importantly, to educate the educators that a lot of information they have been taught is not necessarily the truth.

You’ve been visiting China for over 25 years. How do wine trade people and consumers here react to your ideas?

My first trip was to a wine exposition in Beijing about 1994. After giving my lecture about the principles of personal enjoyment and basics of understanding wine and food interactions–not wine and food pairing!–a Chinese wine expert and educator was taking great exception to the information I presented. My point of view was, of course, very different from what this “expert” had been taught himself.

In a later lecture, this same expert asked the presenter, Jean-Guillaume Prats, then with Chateau Cos d’Estournel and now CEO of Domaines Barons de Rothschild, what he thought of my crazy ideas. Jean-Guillaume basically confirmed my principles much to the disappointment of this “expert” detractor.

Over the years, I have made close to one hundred trips to China and have presented to audiences of varied backgrounds and expertise. The people who have attained certain credentials are sometimes very upset–after all this was not in the courses they took or books they read.

Consumers tend to love to be told they should demand experts help them on a personal level. Millions of consumers, educators, experts and people in the trade often wonder, “What is wrong with me? I don’t smell the things they talk about and many times cannot even enjoy the wines that are supposed to be so fabulous!” We are different–and understanding our differences needs to be taught in the very first wine courses anyone attends.

You divide tasters into four groups–tolerant, sensitive, hypersensitive and sweet. What proportions do you find in China and how does it differ from other countries? (Check your vinotype: English / ä¸æ–‡.)

Our first step is to divide human beings–not “tasters”–into the four basic sensitivity groups. Since we also work with experts in the field of genetics, we can then take our own research into account and correlate the data to other countries. Basically the breakdown of the four sensitivity groups for Caucasians is:

- Sweet vinotypes: 25 percent of the population, with about 70 percent female and 30 percent male.

- Hypersensitive vinotypes: 25 percent and about evenly split between female and male.

- Sensitive vintoypes: 35 percent, slightly more males than females.

- Tolerant vinotypes: 15 percent and almost entirely male.

In China, and Asia in general, there is research indicating that while 50 percent of Caucasians are sweet or hypersensitive vinotypes, that number for Chinese is higher, in the range of 70 percent. Meaning that the overemphasis on red wine may be costly in terms of creating wine consumers, as opposed to experts, that simply enjoy wine as a delicious beverage.

I always find it interesting when people say a wine pairs with “Asian food”, which might cover anything from sushi to bibimbap to curry to nasi goreng, or “Chinese food”, which is diverse, from fiery Sichuan to delicate dimsum. What’s the best way, especially for people who aren’t involved in the food and wine scene, to get their minds around all this?

Just forget the entire wine and food pairing mess! It is not how wine was enjoyed in Europe and it is out of control. French cuisine covers the same gamut of flavor, including all sorts of acidic, sweet, grilled, steamed, roasted or stewed foods. In fact, “Service a la Francaise†is not practiced today even in France, and basically all of the dishes were served at once just as you do in a great Chinese banquet.

This is an area where things are totally out of control–and the “experts” are making recommendations for things they have never tried, have no understanding of the basics of interactions between wine and food, and worst of all may be recommending wines the individual may never like due to their unique genetics and predispositions. A large part of the book is focused on the background for all of this and easy demonstrations that demolish what we are told from the books and educators, such as “red wine goes with red meat.” Drink the wines you love with the foods you love–“match the wine to the diner, not the dinner.”

Yes, I’ve gone to many multi-course wine dinners in China, where guests get a course, paired to a wine, then it’s on to the next course. But when I go out with friends, the meals tend to family-style, and people share and switch back and forth.

My suggestion is always the same–demand wines you love, drink what you think will be most enjoyable. If you are eating family style, consider the preferences of the guest and maybe order a couple of very different wines. In France, Spain or Italy, if a wine was too strong, it was okay to add a splash of sweet liqueur, a sugar cube or fruit juice. Let’s bring back that tradition!

And if it is appropriate, share about what happens when you are trying combinations. Try one wine and different dishes, with the understanding that one person may say, “Wow, this was a terrible combination,” while others may find it delicious. Explore. In the book you will learn how the vinegar and soy sauce on the Chinese table can play the same role in turning a “bad” combination delicious just like the salt and lemon on an Italian table. Try things, talk, have fun. And if you want Moscato, dry white wine, or a strong red wine with everything, then do it.

Umami. What’s your take!?

Umami is a Japanese word for a very important primary taste humans perceive. At a technical level it is the taste of glutamate–MSG is both salty and umami taste–and compounds called nucleotides play an important role in intensifying this. All cuisines have ingredients and techniques that have evolved to intensify umami taste.

In terms of evolution, humans are naturally attracted to umami taste–it leads us to nutritious safe foods with complete proteins. Thirty years ago, I started introducing what I was learning about umami into my lectures–you would not believe the anger and push back that I received! Modern sensory scientists now believe there are hundreds, if not thousands, of tastes, but they generally fall into the categories sweet, sour, salty, bitter and umami. This is another area where the wine education programs, books and “experts” need a lot of revision and updating!

Speaking of updating, how did your book’s translation come about?

A number of years ago I received a call from Danni Lin. Danni was living in Seattle and her hometown is Harbin. She was taking WSET classes at Napa Valley Wine Academy and bought a copy of my book. Danni explained she was developing a wine brand for China and thought the concepts would potentially make a huge impact on wine enjoyment and expand wine consumption in China.

We have worked together for a long time now, and Danni was responsible for having the translation and publication realized. I had also worked with my co-writer, Sasha Paulsen, and we spent a lot of time working on putting the information into a context that we hope Chinese will find more relatable. For example, there is a section with comparisons of different teas to wine styles. Instead of comparing wine smells to Western fruits and spices, the book points out that Moscato, for example, has the same smell molecules as lychee or longan fruit or jasmine flowers. Danni was able to find the publisher, book designer and finally we are in print!

Note: Here is the QR code for more info / to order the Chinese version of the book. See here for the English version.

Grape Wall has no sponsors of advertisers: if you find the content and projects like World Marselan Day worthwhile, please help cover the costs via PayPal, WeChat or Alipay.

Sign up for the free Grape Wall newsletter here. Follow Grape Wall on LinkedIn, Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. And contact Grape Wall via grapewallofchina (at) gmail.com.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.