By Jim Boyce | Little is written in English about Pigeon Hills (西鸽酒庄), a new project that might well transform China’s promising Ningxia wine region. Many trade visitors to Yinchuan have heard the “small winery, large area” spiel in recent years, the idea of settling a 200-plus kilometer north-to-south swath of Ningxia with boutique operations. There are at least 86 functioning wineries there now, most of them small, many racking up medals at contests here and abroad.

Pigeon Hills is not part of that. The powers that be, concerned those medals haven’t meant much higher sales, saw the need for some big leading brands, too. Pigeon Hills has risen from the dust in less than a year with 10 million liters of tanks, a fermentation capacity of 6,000 tons and cutting-edge equipment.

Call it an attempt at a Chinese Penfolds, at a widely-known brand that consumers trust—and trust is a key issue for local producers as they get crushed by imports—and that makes both top-flight labels and large amounts of inexpensive wine for middle class buyers.

The project is headed by Zhang Yanzhi (å¼ è¨€å¿—), a Bordeaux-trained winemaker and founder of importer / distributer Easy Cellar, which handles the likes of Penfolds Max. That gives Zhang an outlet for building the Pigeon Hills brand and moving its wines. The financial means are there, too. Chinese reports state Pigeon Hills is backed by 300 million rmb raised with the help of the region’s Wine Trading Expo Center.

Liao Zusong (廖祖宋) is in charge of operations. A former assistant winemaker at Shanxi’s Grace Vineyard, he has spent time at Bass Philip and Mollydooker in Australia. More recently, he has made wine at another of Chang’s Ningxia projects, Guanlan. (Liao is also a translator, including the book The Taming of the Screw by Tyson Stelzer.)

Liao met me at Yinchuan airport on a sunny April day this year and we headed to Pigeon Hills. I’m not sure who was more tired. A party the night before meant no sleep for me except what I caught on the morning flight. And Liao had the day-to-day weariness of managing a huge project and being a new father. A friend of Liao’s happened to be on the flight and joined us.

We first recharged with lunch in Minning, a historically relevant town named for Fujian province (also known as Min) and Ningxia. China’s President Xi Jinping visited the region in 1997 as a Fujian official, on a mission to reduce poverty, and one idea was to relocate residents to Minning from harsher areas. The vineyards we drove to after lunch were planted the same year, making them ancient by local standards and seemingly shrouded in fate.

Pigeon Hill only just started using those vineyards of some 1,000 hectares. They were also used for the second Ningxia Winemakers Challenge, held 2015 to 2017 with 48 contestants from 17 nations. Backed by the wine authorities, that project gave each contestant three hectares of grapes and leeway on harvesting and wine-making. The ensuing wines showed the diversity possible from this land.

(I recently dreamed of clever Ningixia people sitting around a table and repeatedly tasting those 48 wines, made by their “old friends” from abroad, in an attempt to squeeze out the secrets of the vines. Maybe to make the “Grange” of Pigeon Hills?)

Anyway, if Pigeon Hills is able to make good inexpensive wine, say that retail for rmb100 or less per bottle, what happens to those boutique wineries with far younger vines and higher prices? Does Pigeon Hills increase consumer demand and, in turn, help everyone? Or does it create price pressure that wipes out some smaller players?

We arrived at the vineyards to find workers uncovering the vines, waking them from the five-month dirt nap that offers protection against the cold dry winter weather. Burying and uncovering vines is a time-consuming process that kills some plants and adds another challenge to making good inexpensive wines for the broader market.

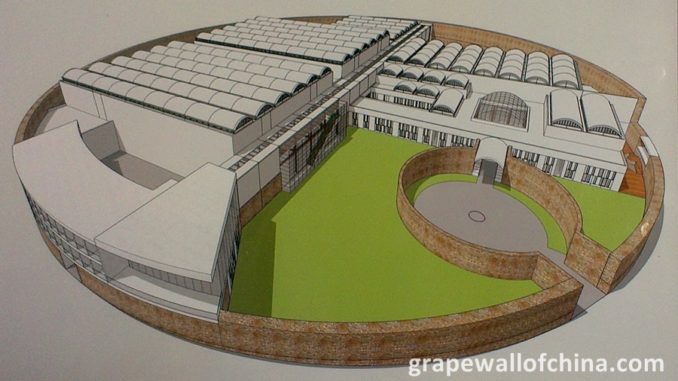

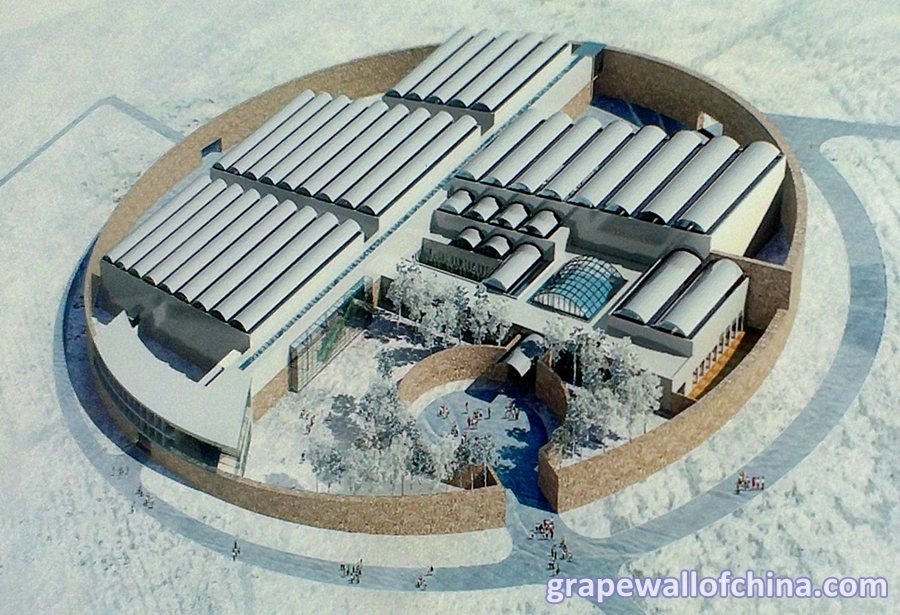

We then drove to the winery, passing a plot of newly planted Malbec. Pigeon Hills is a circular site, with the perimeter defined by a high stone wall. Inside the grounds, a crew had used a backhoe to lay large trees lengthwise on an empty plot. A scene defining work in progress.

We headed into the winery. The main production area has a 4,000-ton capacity, with 42 each of 40-ton and 60-ton tanks. A smaller area next door, for superior wines, has plenty of 10-ton and 15-ton tanks.

Liao said a thousand barrels were already in use for the 2017 vintage. He showed us loads of equipment, from extra-wide sorting tables to a German press to a phone-based tank monitoring system by New Zealand company VinWizard. (A tight relationship exists between Pigeon Hills and New Zealand, with that country’s ambassador to China visiting in February.)

We then got down to an impromptu tasting: Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Gernischt, Petite Verdot, more. From barrels, from tanks. Swirling, sniffing, sipping. Liao seemed distracted, an understandable position given he was trapped tasting juice with a dead-tired Canadian instead of checking off a long list of tasks. We wrapped things up.

Liao would need all his energy to complete the tasks ahead, ones that could have repercussions not just for Pigeon Hills and Ningxia but for China wine as a whole. As if a signal of the pace required, we left the winery an hour after entering to find six trees already planted in the yard.

Note: This is just a snapshot of Pigeon Hills. Much work has been done since my visit on this and on other projects to promote Ningxia wines in a market where consumer often find the prices too high, if they trust Chinese wines in the first place. More on Pigeon Hills soon.

Grape Wall has no sponsors of advertisers: if you find the content and projects like World Marselan Day worthwhile, please help cover the costs via PayPal, WeChat or Alipay.

Sign up for the free Grape Wall newsletter here. Follow Grape Wall on LinkedIn, Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. And contact Grape Wall via grapewallofchina (at) gmail.com.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.